Saint Hildegard of Bingen – First German Poet and Doctor of the Church

From April 13-15 this year, I traveled to Rüdesheim with my Buddhist friend and writing student Teresa Jansen as the only participant. I could have imagined a small group, but finally being two and three for half a day was really good! After Teresa had come clean for herself and me with a few words (see * below), I asked myself once again: Had I been kidding myself? After four months distance I can say: No. I admired Hildegard of Bingen already before I finally realized the longer planned pilgrimage. I was inspired by her courage and astuteness, her creativity and independence. Since Lisa Becker-Saaler and I offered the women’s writing school in a convent – more on that below – we penetrated deeply into what we now see as the partial freedom of our writing medieval sisters: We who were as hungry for knowledge, our own research, life, reading, learning, writing as many of the convent women. The highest symbol of her freedom as a woman consisted in the thick book Hildegard holds in her arms instead of the baby Jesus (a statue) and two statues showing her with pen – in her hand and lying in front of her. Today’s women, including Lisa Becker and me, realized bodily AND spiritual motherhood. – Fortunately, Teresa did not regret our request – we did not stay only in the churches and abbeys!

That of all places, the notorious wine and tourist town on the Rhine has several spiritual testimonies of Saint Hildegard to offer, I did not know until recently. I probably would have gotten off the train in Bingen and would have had to decide whether to go to the museum first – I’ll come back to this later (**) – or to take the ferry to Rüdesheim.

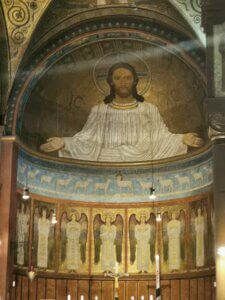

When I made the first call in Rüdesheim in January to one of the few travel agencies still available in Germany, they pointed out the winter break. Not until April would the sites important to travelers open: Hotels, pubs and cafes, stores. The churches will probably be open all year round for the residents – or are there not enough “residents”? we thought. We booked a middle-class hotel, family-run, not far from the road leading up to the Hildegard von Bingen pilgrimage church. (This is the church with the famous and impressively beautiful enlarged mosaic on the altar wall). But also to the abbey up by the vineyards you could either walk well, or take the chairlift just outside Rüdesheim – a boat would be able to take us there if we didn’t want to walk. The price of the hotel was a post-Covid price, I had probably only paid that much once, if ever, for bed/breakfast. But it was going to be worth it.

The drive, first by local train to Andernach where Teresa was already waiting for me, then by her car on the slow but varied idyllic route right along the river, is longer than suspected and absolutely worth it. These views of the winding river, of very differently shaped vineyards and as if thrown, tiny seeming villages right on the water …, that is simply enchanting and not always so well experienced from the train.

The drive, first by local train to Andernach where Teresa was already waiting for me, then by her car on the slow but varied idyllic route right along the river, is longer than suspected and absolutely worth it. These views of the winding river, of very differently shaped vineyards and as if thrown, tiny seeming villages right on the water …, that is simply enchanting and not always so well experienced from the train.

A still sparsely visited Rüdesheim welcomed us, with extremely obliging inhabitants and service providers. Where one café nestles next to another, on the banks of the Rhine and in one of the most famous alleys, we could vividly imagine the hustle and bustle in the coming months, especially on weekends. But so… – it was just relaxing and wonderful. Renovated half-timbered houses around large courtyards, richly decorated towers and doors, in black, white and red – there was so much to see!

However, I was most interested in the places where the nun worked, and so we were drawn to the sanctuary on the day of arrival. Thank you, dear Teresa, for going through all of this without a fuss! Our steps had already slowed down, we had walked in silence from the hotel, and in the church we were the only visitors. After we got our bearings, I stopped at several sculptures as well as a photo exhibition of the fire and reconstruction of the church, and then walked toward the golden “chest” that stood in the center of the sanctuary and contained the bones of Hildegard. Bones are said to be able to store strong power, I knew from testimonies of indigenous peoples. Perhaps this is a bridge to understanding relic veneration. A good friend of mine, who would be joining us on the 14th, spoke of a great radiance he and his girlfriend had felt on a visit to this very place.

However, I was most interested in the places where the nun worked, and so we were drawn to the sanctuary on the day of arrival. Thank you, dear Teresa, for going through all of this without a fuss! Our steps had already slowed down, we had walked in silence from the hotel, and in the church we were the only visitors. After we got our bearings, I stopped at several sculptures as well as a photo exhibition of the fire and reconstruction of the church, and then walked toward the golden “chest” that stood in the center of the sanctuary and contained the bones of Hildegard. Bones are said to be able to store strong power, I knew from testimonies of indigenous peoples. Perhaps this is a bridge to understanding relic veneration. A good friend of mine, who would be joining us on the 14th, spoke of a great radiance he and his girlfriend had felt on a visit to this very place.

Each of us looked for a place to meditate. This painting on the altar wall, enlarged many times, probably the best known of St. Hildegard, which expressed one of her visions, is simply stunning in its creative power, statement, beauty. I couldn’t get enough of the circle that protruded a little beyond the rectangle below: I imagined the circle as THE symbol of femininity par excellence, and perhaps Hildegard’s creativity is expressed here in representing the yin-yang symbol known today in her way: less fluid and dynamic than that one, but powerful. Isn’t that what we lack in “our” Abrahamic religions? Anyway, I let the special silence of Eibingen, which is the name of the district with its church, and the soft-strong blue tones of the wall, of the rectangle of the painting, with the overlapping circle, have an effect on me. I can do more and more with the figure of Christ, he is – Buddhist thought – the Bodhisattva, who serves all beings and is ready to witness this through all lives. https://g.co/kgs/bUoPLz

Each of us looked for a place to meditate. This painting on the altar wall, enlarged many times, probably the best known of St. Hildegard, which expressed one of her visions, is simply stunning in its creative power, statement, beauty. I couldn’t get enough of the circle that protruded a little beyond the rectangle below: I imagined the circle as THE symbol of femininity par excellence, and perhaps Hildegard’s creativity is expressed here in representing the yin-yang symbol known today in her way: less fluid and dynamic than that one, but powerful. Isn’t that what we lack in “our” Abrahamic religions? Anyway, I let the special silence of Eibingen, which is the name of the district with its church, and the soft-strong blue tones of the wall, of the rectangle of the painting, with the overlapping circle, have an effect on me. I can do more and more with the figure of Christ, he is – Buddhist thought – the Bodhisattva, who serves all beings and is ready to witness this through all lives. https://g.co/kgs/bUoPLz

After sitting on the forecourt for a while, we walked back in silence, each at our own pace. First we had a snack at an open “Asian” restaurant, then we met at 20:00 for meditation and dialogue in my hotel room. Such an end to the day is very nourishing for me, I think we both felt that way. The agreement was to get together again the next morning, 4/14, for morning meditation.

So wonderful not to meditate alone on my birthday morning! Teresa presented me with a hug, a tiny bouquet of flowers, a beautiful card and the freshly published complete edition of the texts of Etty Hillesum: this increasingly well-known Dutch mystic, who waited with many other Jews in Westerbork for transport to certain death in an extraordinarily conscious and composed way. In her composure and existential foresight, the 29-year-old reminds me of Janusz Korczak, Victor Frankl, Jacques Lusseyran, the Scholl siblings, Simone Weil, Dietrich Bonhöffer, to name just a few outstanding examples. In its lyricism and condensed wisdom, however, it stands uniquely.

After a delicious and extended breakfast, we listened to an interesting talk by a guide who was already waiting in the church. He told us how we should imagine life in the Middle Ages, about the plague in Bingen and how they tried not to bring it to the other side by ship. We learned many things about Hildegard’s life and were able to ask questions, which expanded the talk into an inspiring conversation. The weather was…imperial weather, or so it will have been on Easter Monday, 4/14/1952.

Hildegard came from a wealthy noble household and at the age of eight, as was customary at the time, was given as a tenth child, together with her older, later teacher, to the monastery of Disibodenberg, inhabited by Benedictine monks, for religious education (‘inclusorium’). She later founded her own monastery, where she applied less strict religious rules than was generally the case, risking and fighting through disputes with male authority figures.

I now make a jump and leave the further stations of her life unmentioned, because I have not yet internalized them myself and one can easily read them at “wikipedia“. Anyway, Saint Hildegard was and is considered the first representative of German mysticism of the Middle Ages, also the first poet. (I heard this also from Roswitha von Gandersheim, who was abbess in my birthplace Bad Gandersheim, to my knowledge actually the first). Her works deal with religion, medicine, music, ethics, and cosmology. She was also a valued advisor to many high spiritual figures, such as Bernard de Clairvaux.

Especially on this birthday I remembered the time when together with Lisa Becker, poetry pedagogue like me, journalist, nutritionist, I created the concept for the women’s writing school KALLIOPE in 1998, drafted texts for flyers and for the eight modules + one introductory module, which remained almost unchanged after Lisa’s death. On the first page of the elaborate flyer was written “SCIVIAS = Know the Ways”, title of the main work of Saint Hildegard. It had deeply inspired us at the time, Lisa and I, that our writing ancestor, as mentioned earlier, had been depicted in a sculpture with a quill instead of the infant Jesus. Since we were also studying feminist literary studies for the writing course, the women mystics of the Middle Ages were part of the students’ recommended reading, or we quoted from various works on the subject. The religious women were among the few women who could write and read at all, acquired education, learned languages and arts, and, like Hildegard, conducted correspondences with scholars.

Did we have anything to do with the God-fearing women who wanted to escape marriage and motherhood, sometimes sexuality, loved learning and teaching?

QUOTES from: Annerose Sieck: Women Mystics – Biographies of Visionary Women. S. 23

“The medieval marriage was, after all, according to all legal sources, a relationship of subjection, which allowed a man to make his wife simply by physical force into an obedient creature without will of her own.” (Peter Dinzelbacher) p. 19

“Throughout history, mysticism has been mostly a lay matter – and a woman’s matter. Perhaps that is precisely why they were able to listen inwardly.” (Andreas Ebert). S. 38

“Women who belonged to the nobility had hardly any chance to work. They were involved in the family and were responsible for raising the children and running the household, which included staff. Some managed to have influence at the political level.” Mentioned here are: Theophanu (d. 991), Eleanor of Aquitaine (b.c.1120), Blanche of Castile (b. 1188). S. 23

“Another reason for the attraction of the monasteries was the excellent opportunities for education and intellectual-literary activities offered to women. A not insignificant role was also played by the care aspect, which was especially important for parents. The aptitude and inclination of girls was often not asked about.”

And what did all this have to do with us school founders, and if so, what was it exactly?

One thing was obvious: Since we were fortunate enough to have a long-term – it was to be twelve years! – the convent of the Waldbreitbach Franciscan nuns in the Westerwald as the venue for our “school”, it was obvious to also deal with the joys and sufferings of the nuns: I as a native Protestant, phased out of the church, equally close to liberation theology, feminist theology and Buddhist teachings, humanism and psychoanalysis. After the birth of my daughter Lisa Denise, I rejoined the church. My colleague and friend Lisa Becker (later she married and was then called Becker-Saaler) was raised Catholic and travelled around England, joining story telling circles, following in the footsteps of the Holy Grail. England at that time, just like Ireland and France, was much further along with “creative writing” than we are in Germany. Prof. Lutz von Werder, my teacher, was to become a midwife for the “New German Writing Movement.” Later, my friend would fall in love with an evangelical pastor on one of the train rides to Hagen or back from there, where she was doing a Bachelor Journalism course in “Journalistic Writing”, and have twin girls with him, after years of moving, getting to know each other, and finally getting married in Hessen.

What did the encounter with Hildegard, who was canonized centuries later, bring about? One thing can be said, I think: she touched me. On the second evening in Rüdesheim, after the evening meditation, we asked ourselves: Is there really such a big difference between the hatred of women then and now? If we consider how many attempts, how many centuries full of renewed petitions to the Pope and again and again ignorance had to pass until this versatile educated, visionary gifted scholar was finally taken so seriously that she was honored as a Doctor of the Church. Until her reforms of religious rules were accepted. Until her visions were considered groundbreaking for Christians, for people…, and if we consider many a politician, writer, leader, and remember how difficult it was made for these women, even today, to earn well, to be heard, to be transferred or elected…, then she, abbess of several monasteries, was just very early to have to fight – similar, by the way, to Christine de Pizan.

How challenging, attractive, yes, and therefore also threatening, her intrepid intelligence must have been, at least for some churchmen, so that they would have preferred to banish the memory of the pious ancestress. How much might the self-worth of monks have depended on the humiliation of nuns? And, on this background, how amazing the resilience and daring of women not to give up, even here, in the patriarchal monasteries! Both of us, Teresa and I, by the way, are also latecomers to Intuitive Writing, an – at least at first – unintentional, expressive writing. a writing “from the whole body,” as I often say or write.

Her financial potency had helped the noblewoman Hildegard, for she could acquire land and buildings. In this respect, quite a few women owed refuge and education to their noble sisters. That had not been so clear to me until now. Often women also needed the encouragement and solidarity of at least one male colleague or superior, in modern terms, in order to be able to take their rightful place on the basis of talent, training, vocation. Which, by the way, applies just as much to Buddhism.

Delicious was the cable car ride we took after a walking tour through the half-timbered buildings in Rüdesheim: Floating high above the gently rolling vineyards that reach up to the abbey. The abbey, too, lived and still lives from winegrowing; I had not been aware of that. From which the tourist image of the place can be understandably explained. I found the rest of the walk, from the cable car station at the top to the abbey, which soon appeared in the distance as a dark, two-pointed symbol, magical. Magical to walk again in the warm April sun. Magical the blue, unclouded sky above the blue of the river, the green of the hills, the white and gray of the larger and smaller stones on our way, which easily started rolling under our feet, at first still along a sparse grove.

Along a long wall of old stones we walked the last hundred meters or so to the abbey, looking for the café. There we had an appointment with Jürgen König, my friend of many years.

In the shady courtyard of the café, coffee and cake did real good, and we had plenty to talk about, even when Jürgen soon joined us. I remembered that the majority of the women participating in the writing school in Waldbreitbach were not religious. Some women had had terrible experiences in regular school, boarding school or home, and all difficult topics, including this one, lent themselves to being processed in and into texts. The persecutions and killings of witches, in addition to the two dictatorships, the Holocaust, and the Berlin Wall, still weighed on us women in a certain way and provided a powerful self-censorship, which had led to more or less rigid writing blocks or inhibitions in all of us.

In the shady courtyard of the café, coffee and cake did real good, and we had plenty to talk about, even when Jürgen soon joined us. I remembered that the majority of the women participating in the writing school in Waldbreitbach were not religious. Some women had had terrible experiences in regular school, boarding school or home, and all difficult topics, including this one, lent themselves to being processed in and into texts. The persecutions and killings of witches, in addition to the two dictatorships, the Holocaust, and the Berlin Wall, still weighed on us women in a certain way and provided a powerful self-censorship, which had led to more or less rigid writing blocks or inhibitions in all of us.

Punctually at 5:30 p.m., we found ourselves in the church room of the Benedictine Abbey high above Rüdesheim for evening devotions. I no longer remember whether anyone preached. But from the gallery sounded the bright, Gregorian choral singing, which I had already learned from a CD with Hildegard’s compositions. Perhaps it was due to my birthday, the weather: this choral singing from the gallery without seeing anyone touched me as unearthly. (It should not have been a played CD…) The resonance of the Zen exercise, silence and sound in an abbey, the vastness of the sky and the landscape, undulating to the horizon, merged in me into an ocean on which I have been taking surfing lessons for decades.

Punctually at 5:30 p.m., we found ourselves in the church room of the Benedictine Abbey high above Rüdesheim for evening devotions. I no longer remember whether anyone preached. But from the gallery sounded the bright, Gregorian choral singing, which I had already learned from a CD with Hildegard’s compositions. Perhaps it was due to my birthday, the weather: this choral singing from the gallery without seeing anyone touched me as unearthly. (It should not have been a played CD…) The resonance of the Zen exercise, silence and sound in an abbey, the vastness of the sky and the landscape, undulating to the horizon, merged in me into an ocean on which I have been taking surfing lessons for decades.

*)

Teresa Jansen: Looking backwards to the experience with St. Hildegard

Why

are you

silent? Or have

I closed up to

you?

Maybe

later on.

Or maybe not.

Why should that be

bad?

It

doesn‘t matter

at all. Not

even pity. Nevertheless: A

great time!

Monika Winkelmann: as above

How

much courage

belonging to God

God: this often uncomfortable

Truth

Longing

for beauty

and truth respectively

both unseparated makes me

happy

First

Virginia Woolf

claimed for own

room, income, for „Shakespeare‘s

Sisters”

**)

The Museum am Strom on the other side of the Rhine, we entered the next, on the day of departure, only briefly to take a look inside, use the bathroom and pocket a flyer. On this side of the Rhine, too, there was God-fearing life. We glimpsed all that had to make way for more interesting construction than places for religious, prayer and retreat, celebration, hope for healing, for transformation. I will be back. It is only a 10 minute walk from the Bonn-Mainz train station.

***)

15.9.2023: Hildegard von Bingen exhibition at the Frauenmuseum Bonn

I was happy to see this announcement. My intuition is right. I am very excited to see what Marianne Pitzen, founder of the Women’s Museum, and her fellow artists have to convey artistically to us women and, of course, to progressive men.